A deep brown skinned man reclining naked on a comfy bed stares me right in the eyes with a look on his face that is both frank and indifferent. His penis halfway between flaccid and hard; a delicate pale-yellow flower peeking out from behind his left shoulder, around ear height. Walking away from the scene there’s a second man, wiping his chest with a rich fabric and providing a glimpse of his perky bum on his way out. The whole setting seems vaguely familiar and just when I’m about to get frustrated by an unfulfilling feeling of déjà vu, I notice the slipper hanging loosely from the protagonist’s foot. With this last hint the reference becomes crystal clear and in hindsight I don’t understand why I didn’t see it right away.

Richie Nath’s painting mirrors Edouard Manet’s controversial 1863 painting Olympia, the obvious twist being the replacement of the sex worker by an Indian man in a post-coital scene. Just like Manet, Nath introduces an unapologetic character, self-aware and confident. The stunning effect the painting has on me goes deeper than the initial satisfying feeling of simply understanding the reference. I know this scene. In fact, as a gay man, I have actively engaged in different versions of this setting, playing the part of either of the two characters. It is thrilling to see these intimate scenes of my own story, my identity even, being depicted in such a direct yet gracious manner.

It’s something you just don’t talk about

I encountered Nath’s work browsing through Instagram and I immediately became intrigued by the mystical elegance of the images on his page. There was something about the carefree manner of the characters that inhabited his paintings that appealed to me, but I couldn’t quite grasp what it was. One week later I’m talking to the upcoming artist from behind my screen; he agreed to meet me on Zoom to talk about his work and the ways in which he expresses his queerness through art. The painting that had such an impact on me is ironically titled Do you have a girlfriend?, after the dreaded words many gay guys get so tired of hearing during their adolescent years. “It’s a question I used to get all the time”, he says. “In Myanmar homosexuality is sort of tolerated, but most people tend to act as if it simply doesn’t exist. It’s something you just don’t talk about.”

Nath, now 26 years old, grew up in Myanmar’s largest city Yangon. Being gay and of half-Indian descent, he often felt out of place. With homosexuality still being officially illegal in the country, he often wanted to hide away, concealing the parts of him that would be considered effeminate or queer. Moreover, his darker skin tone acted as a constant reminder of his Indian heritage, always making him the Other. “There are many ethnic groups in Myanmar and for the most part there is some form of mutual respect, but Indian migrants are usually looked down upon”, he explains.

In his youth, he would often make up elaborate stories in his head, drawing inspiration from the Southeast Asian, Greek, and Egyptian myths and legends he would hear and read about. “I have an overactive imagination”, he laughs, and goes on describing how he would act as the protagonist in these private fantasies, roaming around in an imaginary world, encountering exciting male characters that would take an interest in him. Here, he could safely explore the parts of his identity that he would otherwise carefully hide. “Already in middle school I used to draw somewhat erotic scenes between two men, but always in secret and I would make sure to quickly and thoroughly destroy them when they were finished.” Although Nath fantasized freely in the confinements of his mental world, it would never even occur to him that one day he might share these personal stories with the world.

A single story

In her now-famous 2009 TED Talk The Danger of a Single Story, Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie explains that, as a kid, she used to write stories of blue-eyed, white children, eating apples and playing in the snow, and how these were strangely incongruous with her own childhood, growing up surrounded by people of color, eating mangoes and never seeing a single snowflake fall out of the sky. Her idea of a story worth telling was shaped by the fact that she only had access to American and British texts, in which her own culture was severely underrepresented or even nonexistent. It wasn’t until she discovered African writers that she realized girls like herself could exist in literature. She explains how always hearing a single narrative makes it hard to imagine that different versions are even possible. The only available and therefore ‘original’ version is automatically considered to be the ‘right’ version. This whole notion can easily be transposed to the experiences of Nath, and with him countless gay people worldwide for that matter, growing up in a conservative, heteronormative society, where every romantic story in (pop) culture, art and day-to-day life seems to revolve around a male-female relationship.

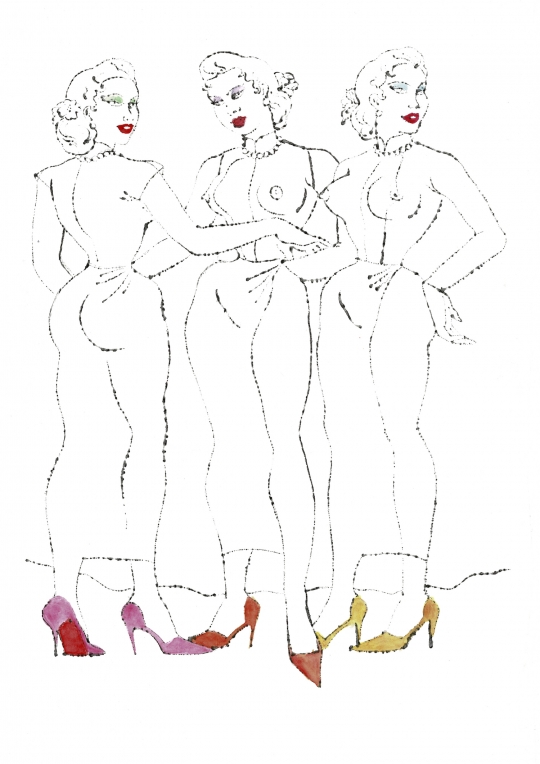

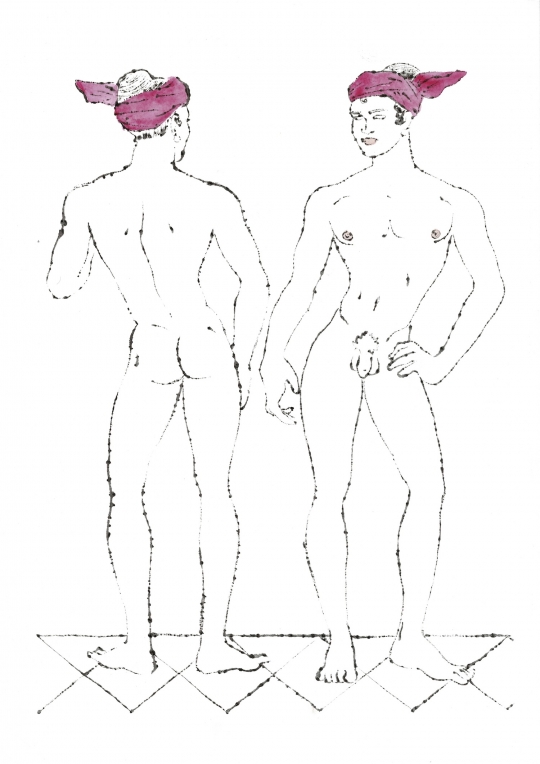

For Nath, an important alternative story presented itself when he moved to Britain to study at the London College of Fashion, where he encountered the work of Tom of Finland. He became enthralled by the highly masculinized homoerotic illustrations. If you’re not familiar with them: imagine buff guys in tight-fitting jeans that show a clear outline of their unnaturally bulky crotches, eyeing each other with an unvoiced promise of a steaming encounter later on. Tom of Finland purposely provided these caricatures with exaggerated, typically masculine traits while overturning that one male characteristic that, in our heteronormative society, is usually considered the most fundamental: being sexually attracted towards women. These confident, muscular sailors, soldiers and lumberjacks stood in high contrast with the image of ‘the gay man’ that prevailed when Tom of Finland started his career in the late 1950s: that of an unassertive, effeminate, heavy-hearted and delicate man. In that way, his work was both controversial and revolutionary, and presented a completely new version of the queer man. Now, seventy years later, his illustrations have achieved cult-status in the queer community and can be found on posters in most gay bar bathrooms and homoerotic shops worldwide. For Nath, they opened a whole new world: “Seeing these bold drawings not only influenced my view on gay culture and what a gay man should or could be, they also served as an example of being unafraid to express queer fantasies in art.”

The emperor and the houseboy

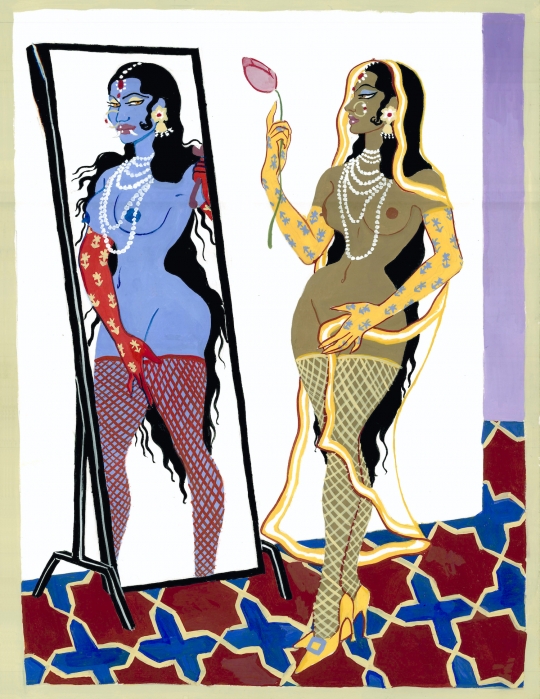

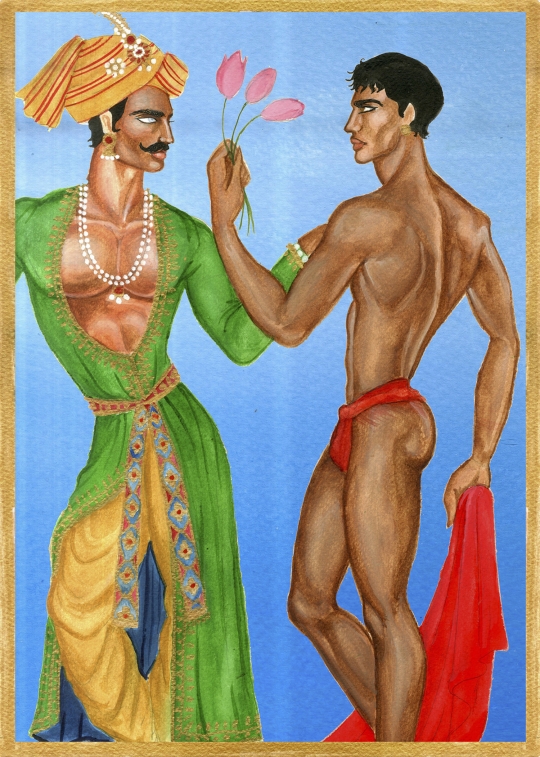

In London, Nath began studying his cultural heritage in more detail. He looked at ancient depictions of the learnings of the Kama Sutra, meant to serve as a manual on how to properly ‘execute love’, offering examples of ways to woo your significant other, of lust-inducing foreplay and sexual acts that would undoubtedly lead to an explosive orgasm. He found intricate Indian miniature paintings of myths and legends, played out by Hindu gods, demons and heroes. He studied Moghul court scenes from the sixteenth- to the eighteenth-century that are full of abundant banquets and romantic encounters in opulent palaces. Even though all these artworks and stories differ in purpose and time of origin, they all have one thing in common: the love between a man and a woman is depicted as profoundly sacred and presented as the ultimate accomplishment in life.

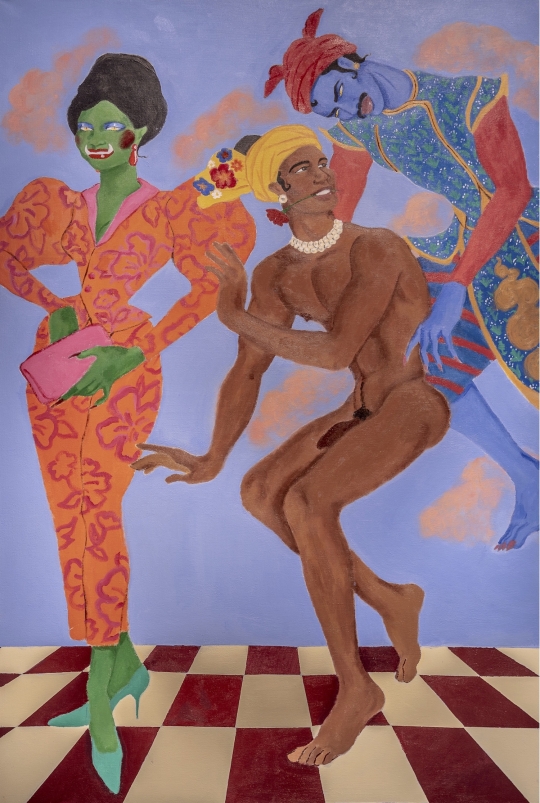

Drawing inspiration from the aesthetics and sometimes even literally introducing a being from these stories, Nath started to create his own narratives on canvas, allowing the characters to play and experiment with their sexual identities and ways of expression. In his versions, the Indian emperor flirts with the houseboy and the princess dresses in nothing more than fishnet stockings, long silk gloves and luxurious pearls. Nath relieves them of their century-old quest for a significant other of the opposite sex and by doing so lets them gain a new sense of self. What strikes me the most: he lets them keep their graciousness and elegance, their new ways of loving are just as heartfelt and sacred.

A visceral experience

In my adolescent years, when I discovered I was never going to live a life of classic Hollywood romance, I went through a period of mourning, convinced that the love reserved for gay men could never be as profound as in the heteronormative stories I would see all around me, simply because I didn’t have access to any examples of that. Even though by now I’ve experienced that that is not necessarily the case, there are still moments where I envy the sacredness of the love story between a man and a woman as presented in art, automatically regarding queer love and queer expressions as somehow subpar. And precisely that is what makes looking at Nath’s paintings such a visceral experience, seeing all these wonderfully diverse figures entering the stage, freely wandering around, unashamed and expressing themselves in any way they feel like.

In the sacred world Nath creates, individual eccentricities are not just accepted, they are celebrated. By depicting these queer characters in the same, delicate, vibrant manner as his Indian predecessors did centuries ago, in the same direct but elegant way Manet depicted his Olympia, Nath manages to integrate queerness in the artistic world without ever being obtrusive. By representing my story, he validates the parts of my identity that I would sometimes rather ignore or suppress, and for that reason I will never get tired of submerging myself in the universe he created.

Richie Nath is part of the group exhibition Notes from the Motherland that opens December 16th at Aicon Gallery, New York. He now temporarily lives and works in Paris, where he applied for asylum, because of the risks of persecution in Myanmar due to the recent military coup.

Ischa Havens works in the field of art mediation and education.