In samenwerking met Ornamenta

Vanaf het moment dat we het bos inrijden, spreken we in boommetaforen. Ik ben met een klein gezelschap per auto afgereisd naar het Zwarte Woud om daar Ornamenta te bezoeken, een hedendaagse kunstbiënnale die deze zomer voor het eerst weer plaatsvindt sinds haar initiëring in 1989. Naast mij zitten Tubelight redacteuren Veerle Driessen en Jip Hinten, en kunstenaar Yvonne Dröge Wendel, die haar werk ‘Black Ball’ op de triënnale toont. Ornamenta-curator Jules van den Langenberg zit achter het stuur. “De kunstenaars die het hier het beste doen, zijn die met wortelzucht”, vertelt hij ons.

‘Wortelzucht’. Het woord blijft de rest van onze korte reis hangen. In een flitsbezoek van achtenveertig uur nemen we de over heuvels en dalen versprokkelde biënnale in ons op. Tijdens de autorit vanuit Amsterdam hebben we elkaar al een beetje leren kennen: Yvonne vertelde over haar vroege jeugd in de regio, waar zij als kind van Nederlanders werd geboren, elke zondag verplicht een boswandeling maakte, en afstak met haar Hollandse accent. Ook Jules heeft op ongeveer elke hoek een anekdote te vertellen. Er is duidelijk sprake van vergroeiing met de regio.

De focus van onze reis ligt op het ‘Inhalatorium’-programma, dat geïnspireerd werd door de ‘frischluft kultur’ of ‘lucht spa’ van het Zwarte Woud. Met haar wijd uitgestrekte bossen staat het gebied bekend om de goede luchtkwaliteit. Rondom lucht, een vermeend gemeengoed, bestaan er in de regio genoeg discrepanties. Op de heuvels is de kwaliteit van de lucht beter dan beneden, in de dalen, en dit vertaalt zich naar sociaal-economische klassen die vrij letterlijk van hoog naar laag verdeeld zijn, zo vertelt Van den Langenberg ons. De curatorenwoning – een voormalig sanatorium met lichtroze balustrades – die hij deelt met co-curatoren Willem Schenk en Katharina Wahl, ligt in een dal, omsloten door dichtbeboste heuvels. Wanneer Van den Langenberg de horizon al een tijd niet gezien heeft, bevalt hem een licht claustrofobisch gevoel.

“Wat doe jij hier in je gezondste levensjaren?”, werd hem gevraagd toen hij in 2021 begon met zijn werkzaamheden voor Ornamenta in de regio. Hij brengt hier sinds de aanvang van het project elke maand een volle week door. Voordat er een curatorenwoning in het leven werd geroepen, logeerde het team veelal bij welwillende mensen uit de omgeving, die ze via briefjes in de bus benaderden. “De meeste mensen uit de streek weten waarschijnlijk nog steeds niet precies wat Ornamenta nou is”, zegt Van den Langenberg met een grijns, “maar ze hebben wel het verhaal gehoord van de ‘jonge mensen’ die overal op de stoep stonden.”

Over de afgelopen vier jaar nam hij niet alleen de rol van curator aan, maar ook die van lobbyist, volksvertegenwoordiger en therapeut. Van den Langenberg beschrijft het curatoriële proces als een soort ‘acupunctuur’, waarbij met kleine presentaties door de jaren heen, als strategische speldenprikjes, uitgeprobeerd werd hoe de omgeving reageerde. Verschillende symposia, onderzoeksreizen en ‘proloog tentoonstellingen’ gingen aan de triënnale vooraf. Langenberg vertelt ons over een vertoning als onderdeel van zo’n proloog-programma in 2021 van Melanie Bonajo’s videowerk ‘Night Soil: Economy of Love’, dat sekswerkers in beeld brengt. Een groot deel van de lokale bezoekers verliet voortijdig de zaal. Maar dat curatie af en toe steekt, benadrukt volgens Van den Langenberg juist de potentie en het verruimende effect van kunst. In veel van zijn werk als curator, zoals bij de Amsterdamse (Nelly &) Theo van Doesburg Stichting, maakt hij middels artistieke interventies de dagelijkse besluitvorming achter gebiedsontwikkeling inzichtelijk.

Het uitgangspunt voor Ornamenta was om de ‘genius loci’, ofwel de ‘plaatselijke geest’, van het Zwarte Woud in de programmering te vangen. Er werd niet van bovenaf een thematiek afgedwongen, maar in plaats daarvan veel afgetast. Door de jaren heen kristalliseerde dit sensitieve onderzoek uit in vijf hoofdthema’s, die de triënnale presenteert als fictieve gemeenten: ‘Inhalatorium’, ‘Bad Databrunn’, ‘Schmutzige Ecke’, ‘Solartal’, en ‘Zum Eros’. De keuze voor het opwerpen van deze imaginaire gemeinden had naast een conceptuele aard ook een praktische uitwerking, legt Van den Langenberg ons uit: “Iedereen in het Zwarte Woud staat pal voor zijn eigen dorp, dus het opwerpen van fictieve gemeenten vergemakkelijkte de onderlinge samenwerking.”

Want hoe activeer je plekken waar eerder weinig rondom kunst gebeurde? Hoe positioneer je hedendaagse kunst in de provinciale periferie, buiten het grootstedelijke culturele centrum? Of, zoals Van den Langenberg het verwoordt, hoe breng je de werelden van de ‘agrariërs’ en de ‘kosmopolieten’ samen? Hoe ga je, als pas aangewaaide curator, om met de uiteenliggende belangen en gevoeligheden van gemeenschappen die hier al zoveel langer zijn dan jij?

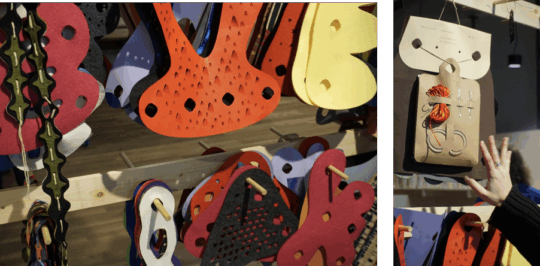

Toen Ornamenta in 1989 voor het eerst georganiseerd werd, vond de triënnale voornamelijk plaats rond het Schmuckmuseum in Pforzheim, de ‘poortstad’ van het Zwarte Woud. Ornamenta spitste zich destijds dan ook toe op ‘Schmuck’, de kunst van juwelierswerk, een industrie met een lange geschiedenis in het gebied. Het initiatief om Ornamenta in 2024 opnieuw plaats te laten vinden kwam van de stad Pforzheim, die een internationaal georiënteerde oproep deed voor curatoriële voorstellen.

De keus viel uiteindelijk op twee Nederlanders, Van den Langenberg en Schenk, en de Duitse Wahl, die al wel wat bekender was met de contreien van het Schwarzwald. Een team van relatieve buitenstaanders dus, maar desalniettemin werd de autonomie van de curatoren hoog ingezet. Die autonomie ging gepaard met grote verantwoordelijkheid, en het ontbreken van enige bestaande organisatorische structuur. Daarbij kwam dat veel cultuurafdelingen van de lokale gemeenten nu voor het eerst met elkaar samen zouden werken. Van den Langenberg, Schenk en Wahl hadden een brede triënnale voor ogen, die de hele regio betrok, en waarbij bezoekers met het openbaar vervoer tussen verschillende plaatsen zouden bewegen.

Om de curatoren bij te staan werd er een adviesraad opgezet met culturele en commerciële spelers uit het gebied. Tijdens de eerste stop op onze Ornamenta-reis ontmoeten wij één van hen: Phillip Reisert de directeur van een fabriek voor goud- en zilver recycling nabij Pforzheim. Reiserts grootste uitdaging als raadslid voor Ornamenta was om mensen uit de regio, die misschien wel niets met hedendaagse kunst hebben, echt bij het proces te betrekken. Dat ging niet zelden gepaard met onenigheid. Zo wilde geen van de dorpen in eerste instantie aangewezen worden als locatie voor het ‘Schmutzige Ecke’ programma; niemand wilde het ‘vieze hoekje’ zijn.

Het speuren naar goud in hoeken en kieren zit in Reiserts DNA. Zijn overgrootvader begon het recyclingbedrijf door de oude vloeren in werkplaatsen van sieradenmakers te vervangen, en als salaris de goudstof te nemen die achterbleef in de spleten van het hout. Het juweliers ambacht ontwikkelde zich midden negentiende eeuw in de regio, en richtte zich op de massaproductie van goedkope, ‘democratische’ juwelen – gemaakt van goud en zilver, maar hol aan de binnenkant – die voor de gewone man betaalbaar waren. Toen sieraden door globalisering elders nog goedkoper geproduceerd konden worden, maakte men hier de omslag naar andersoortige kleinschalige productie met kostbare metalen, van beugeldraden tot uitlaatpijpen. Bij aankomst in de regio brachten de Ornamenta-curatoren lokale familiebedrijven in kaart, waarmee onderzoekende samenwerkingen aangegaan werden.

Familiebedrijven in het Zwarte Woud zoals dat van Reisert zijn onderhevig aan de veranderingen die globalisering met zich meebrengt, en moeten een adaptief vermogen hebben. Maar anders dan grote internationale concerns zijn ze diep geworteld in de regio, en meer geneigd hiervoor blijvend zorg te dragen. Reisert vertelt ons dat veel mensen die uit de regio wegverhuizen, uiteindelijk terugkeren vanwege hun verantwoordelijkheden binnen het familiebedrijf.

Langetermijndenken zit in de aard van het Zwarte Woud, in het langzame groeien van de bomen, stelt Reisert De houtindustrie, die hier decennialang op kop liep (Amsterdam werd gebouwd op palen uit het Schwarzwald), veronderstelt het vermogen om ver vooruit te denken: als je nu een boom plant, hebben je kleinkinderen daar pas profijt van.

De curatoren van Ornamenta 2024 hebben een soortgelijk langetermijndenken aangewend voor hun triënnale, onder andere door het ontwikkelen van een aantal permanente kunstwerken in de publieke ruimte. Anders dan grote biënnales en kunstmanifestaties als die in Venetië en Kassel, die een aantal maanden met veel intensiteit plaatsvinden maar daarbuiten min of meer afwezig zijn, en zich voornamelijk richten op een internationaal publiek, zet Ornamenta in op de duurzame kunstprojecten en creatieve samenwerkingen voor en door de regio. Naast het aantrekken van buitenlandse bezoekers is het investeren in een blijvende verbreding van het kunstaanbod voor de lokale bevolking de ambitie. Het format van Ornamenta kwam in de jaren ‘80 op om steden en regio’s middels cultuur uit te lichten: kunst werd ingezet om mensen naar plekken buiten de culturele centra af te laten reizen. Maar wat blijft er binnen dit model over voor de lokale

gemeenschap, wanneer de meutes weer zijn vertrokken?

Ornamenta differentieert zich van veel andere terugkerende kunstmanifestaties door haar diepgewortelde bewustzijn van het feit dat er altijd al van alles bestaat en gebeurt op een plek waar je iets met kunst gaat doen. De meeste biënnales en triënnales zijn site-specifiek in de zin dat ze telkens plaatsvinden op dezelfde plek, maar spelen niet zozeer in op de daar aanwezige bevolkingsgroepen en geschiedenissen. De meer gegronde insteek van Ornamenta doet me denken aan het onderscheid dat kunsthistoricus en kunstcriticus Amelia Groom aandraagt tussen ‘site-specificiteit’ en ‘plaats-specificiteit’ in hun boek Beverly ‘Buchanan: Marsh Ruins’.

In hun boek bekritiseerd Groom hoe gecanoniseerde Land Art kunstenaars als Robert Smithson en Walter de Maria de afgelegen locaties voor hun site-specifieke landschapsinstallaties als ‘terra nullius’ ofwel ‘leeg land’ benaderen, en stelt de praktijk van de Amerikaanse kunstenaar Beverly Buchanan hier tegenover. De cementen Marsh Ruins sculpturen van Buchanan werden geplaatst op plekken in het Zuiden van Amerika met betekenis in de slavernijgeschiedenis, en verwelkomden de impact van natuurkrachten, die het cement langzaam lieten afbrokkelen. Haar werken zijn zodanig direct verbonden met de socio-historische, ecologische en elementaire condities van het landschap, en kunnen alleen binnen deze specifieke condities ervaren worden. Waar Land Artists de bestaande omstandigheden van een plek grotendeels verwijderden om plaats te maken voor hun kunst, en daarbij weinig consideratie hadden voor de lokale geschiedenissen en bewoners van hun gekozen locaties, is de omliggende context van Buchanans sculpturen onlosmakelijk verbonden met de inhoud van haar werk. De omgeving van het werk wordt hier niet benaderd als blanco ‘site’ of ‘terrein’, maar vanuit alle specificiteit die een landschap tot ‘plaats’ maakt.

De permanente publieke kunstwerken die Ornamenta presenteert hebben een soortgelijke kwaliteit van plaats-specificiteit. Neem het werk Haug, Rainbow Fountain door het Duits-Ijslandse kunstenaarsduo Veronika Sedlmair en Brynjar Sigurðarson, een bronzen sculptuur dat een mist uitstoot die onder de juiste weersomstandigheden een tijdelijke regenboog creëert. De elfachtige figuur is gesitueerd langs de rivier de Enz en is voor de bewoners van Pforzheim vanaf nabijgelegen voetgangersbruggen te zien. Het werk is alleen onder specifieke ecologische condities te ervaren, en speelt zo in op onze hyperlokale verbondenheid met het weer. Ook staat het werk in relatie tot het mystieke karakter van het vaak in nevelen gehulde Zwarte Woud, een plek die vele legendes kent en onder andere het toneel was voor de sprookjes van de gebroeders Grimm.

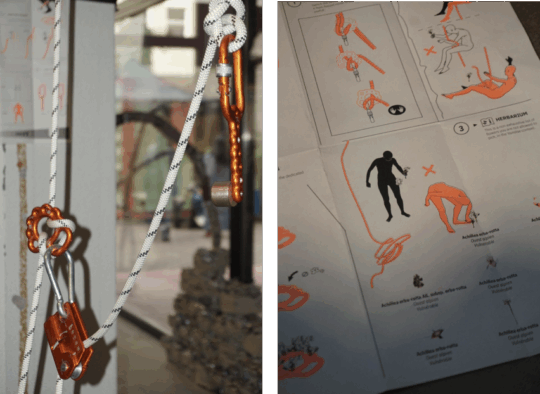

Ornamenta toont het werk van rond de veertig jonge kunstenaars, die over lange periodes nieuw werk voor de triënnale ontwikkelden. Als onderdeel van de productie probeerden zij te wortelen in het Zwarte Woud. Tijdens onze reis bezoeken we de permanente installatie ‘Inverted Paradise’ van Spazio Cura, waarvoor een verlaten, roestvrijstalen zwembad in stukken werd gesneden en als een architectonische Frankenstein opnieuw in elkaar werd gelast naast een woonwijk in aanbouw. Gedurende twee jaar maakte Thorben Gröbel, de Berlijnse maker achter Spazio Cura, samen met Van den Langenberg een inventarisatie van gebouwen in de regio die afgebroken gingen worden. Hij verzamelde de verweesde braakliggende materialen die overbleven, en die, in zijn woorden, een ‘aura’ uitstraalden. Een mengelmoes aan ornamentele elementen was het resultaat: rond het retro chromen zwembad uit de jaren tachtig bracht Gröbel bouwdelen in brutalistische en jugendstil-stijl samen.

Gesitueerd naast de woonwijk in aanbouw, in een grenszone tussen een beschermd natuurgebied en de Aldi supermarkt, functioneert ‘Inverted Paradise’ als een leefkuil voor de jongeren en andere buurtbewoners die hier proberen te aarden. De hangplek kijkt uit op een nabijgelegen bos van elektriciteitstorens in verschillende vormen en maten. Gröbel beschrijft de installatie als een ‘non-typologische ruimte’ die niet binnen representatieve normen past, en daarom plaats kan maken voor gedragingen en gebruikswijzen die in generieke publieksruimtes onwelkom zijn (‘hier plassen alle vrachtwagenchauffeurs’, grapt Gröbel). Het werk contrasteert met de uniformiteit van de aankomende woonwijk, en deed de bouwontwikkelaar in eerste instantie schrikken. Maar de buurtbewoners hebben ‘Inverted Paradise’ langzaamaan omarmd.

“De waarde van dit project is niet gebaseerd op de criteria van een exclusieve groep mensen. Het werk kan alleen slagen wanneer de mensen die eromheen leven het waarderen en er op de lange termijn zorg voor willen dragen”, vertelt Gröbel. Zijn grootste uitdaging was het leren met lokale gemeenschappen samen te werken. Het idee een permanent werk te maken in het provinciale en conservatieve Zuid- Duitsland, stootte de Berlijnse ontwerper in eerste instantie af. Toch besloot hij zijn vooroordelen opzij te zetten en, voor het eerst, uit zijn grootstedelijke bubbel te stappen. Op de bouwplaats van ‘Inverted Paradise’ kwam hij in nauw contact te staan met vaklieden uit de regio.

Deze precaire samenwerkingen werden geïnitieerd en ondersteund door Van den Langenberg, die Görben ‘een meester van subtiel lobbyisme’ noemt. “De basis die Van den Langenberg had opgebouwd in de regio, zijn lokale relaties met sponsoren en politici, maakten het ontwikkelen van een ingebed en relevant kunstwerk mogelijk. Ik kreeg de ruimte om onafhankelijk te werken, maar werd op de juiste momenten gepusht, wanneer het project voor de zoveelste keer niet van de grond leek te komen.” Als kunstenaar wortelen op een reeds onbekende plek gaat niet

zomaar. Er is intensieve curatoriële inzet voor nodig: een diepgaande samenwerking tussen kunstenaar en curator, in tandem. Werken slagen alleen in ‘plaats-specificiteit’ wanneer er een structuur is waarbinnen de kunstenaar de nieuwe omgeving kan leren kennen; een structuur die kennismaking en aftasting prioriteert over voorgenomen plannen.

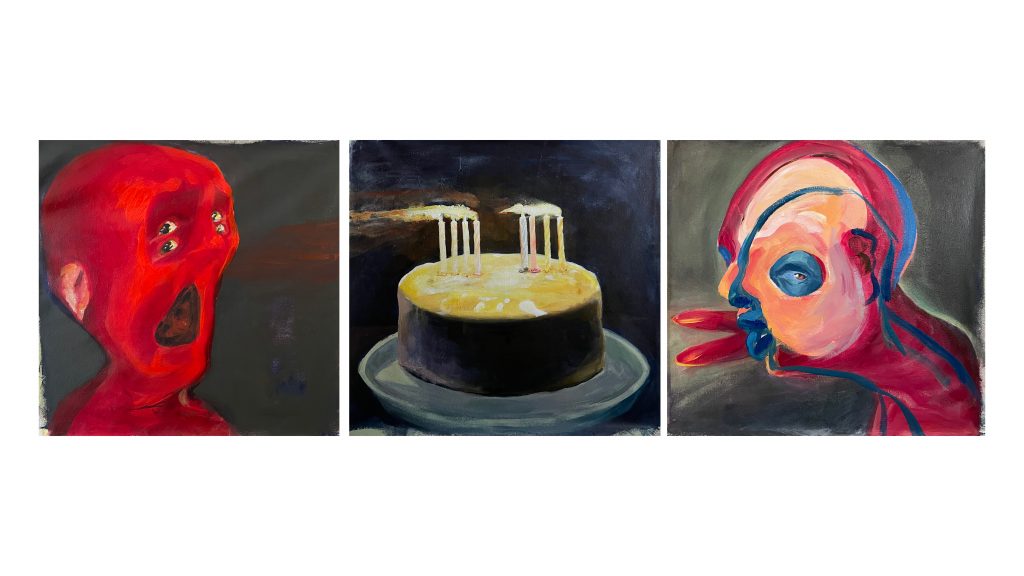

Het is een vraag die keer op keer terugkomt tijdens onze reis: wanneer is Ornamenta een succes, en wie bepaalt dat eigenlijk? Valt het te meten, met bezoekersaantallen en positieve reacties? Ondanks het feit dat er voor het project groen licht werd gegeven door gemeenteraadsleden van de centrumrechtse Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands en andere conservatieve partijen, volgde er na de conceptpresentatie voor de biënnale veel kritiek vanuit diezelfde gemeenteraad en de lokale media. De triënnale zou een ‘elite-project’ zijn, waarvan de inwoners van het Zwarte Woud zelf maar weinig van begrepen. Het is voor te stellen dat de communicatie van Ornamenta voor mensen buiten de kunstwereld vervreemdend is. De marketingcampagne van de triënnale brengt in strakke foto’s nostalgische stijlfiguren samen met high-tech edginess. Mantelpakjes, vr-headsets, koekoeksklokken en vapes vormen een anachronistische

beeldtaal die moeilijk te plaatsen is.

Een kunstwerk waar iedereen bij voorbaat een mening over had, is de ‘Black Ball’ van kunstenaar Yvonne Dröge Wendel, een enorme zwarte vilten bal die met hulp van publiek en begeleiders door het landschap van het Zwarte Woud rolt. “Als er iets is dat Pforzheim niet nodig heeft, is het wel een zwarte vilten bal”, sneerde gemeenteraadslid en Ornamenta-criticus Hans-Ulrich Rülke van de Freie Demokratische Partei in een lokale krant.

Van hevige reacties op haar zwarte bal kijkt Dröge Wendel al lang niet meer op. Sinds 1999 reisde ze met de ‘Black Ball’ naar onder andere Istanbul en Zuid-Afrika, waar ze het gevaarte persoonlijk door de straten duwde. ‘Black Ball’ gaat niet zozeer om het object van de bal zelf, die volgens Dröge Wendel “geen inherente betekenis of functie heeft”, maar meer over waar de bal op stuit. Vanwege de grote hoeveelheid ruimte die de bal inneemt, zit deze al snel in de weg. Binnen de context van het ‘Inhalatorium’-programma roept ‘Black Ball’ vragen op over de relationele dynamiek en onderlinge verbondenheid die openbare ruimte impliceert: objecten circuleren tussen ons, net als de lucht die we inademen.

“Afhankelijk van de situatie is die bal een knuffelding, een wapen, of een vervelend showobject,” stelt Dröge Wendel. “Sommigen rennen erop af, anderen schrikken er juist van. Iemand dacht dat het een atoombom moest voorstellen, of de geblakerde aarde, over honderd jaar.” Gedurende Ornamenta rolt de bal van dorp naar dorp, en de omgang met het object is per plaats anders. Waar de bal in het ene dorp vrijelijk van heuvels mag rollen, wordt elders een politie escorte geregeld. “Ik ben geïnteresseerd in wat een object voor elkaar kan krijgen, naar het gebeuren om zo’n ding heen”.

Speciaal voor Ornamenta werd er in het Zwarte Woud een nieuwe ‘Black Ball’ gevilt, met de hulp van ongeveer zevenhonderd vrijwilligers uit de omgeving. Samen kletsten en zongen ze tijdens het vilten, en werden ze onderdeel van een haast sprookjesachtig verhaal. Tijdens onze reis ontmoeten we een aantal van de deelnemers, die te herkennen zijn aan de kleine zwarte vilten balletjes die ze trots opgespeld hebben. Dröge Wendel duwt de ‘Black Ball’ dit keer niet zelf vooruit; er is een speciale groep begeleiders samengesteld, bestaande uit alumni van de kunstacademie in Pforzheim. We treffen twee van hen, terwijl ze de bal ‘uitlaten’ bij het kuuroord Bad Wildbad. Justus Lietzke en Johanna Heilig nemen net een pauze, en hebben de ‘Black Ball’ geparkeerd naast een idyllisch-uitziende watermolen. We mogen het van ze overnemen, en rollen de bal over paden, bruggen én over onszelf.

Meer dan een omlijnde kunstmanifestatie, is Ornamenta een totaalervaring. Via de website en het Instagram kanaal worden uitstapjes aangeprezen die aan de thematiek van de triënnale gelieerd zijn, zoals een ademhalingsmeditatie, hydrotherapie in een Kneipp-bad, en een diner bij een plaatselijke forellen rokerij. Onze Ornamenta-ervaring heeft een hoog wholesomeness-gehalte, anders dan ik, op basis van de huisstijl van de triënnale, had verwacht. Op momenten is de sfeer zó wholesome, en gericht op ‘selfcare’, dat het een beetje gaat kriebelen.

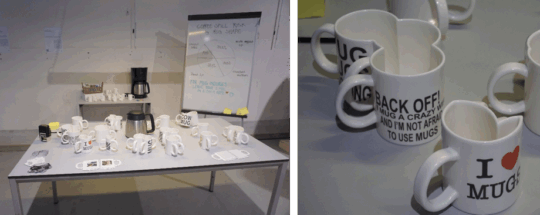

Zoals bij het kunstwerk ‘Mobile Stones’, door kunstenaar Wiktoria Wojciechowska en gallerist David Feulner, dat een serie edelstenen presenteert, gepolijst in de vorm van smartphones. Het werk biedt, in de woorden van Ornamenta, een aanleiding tot reflectie op onze, vaak uitputtende, relatie met onze sociale gereedschappen, en op de emoties die bovendrijven terwijl we klikken en scrollen. Een associatie met de afschuwelijke beelden op social media van de genocide in Palestina is snel gemaakt, maar wordt nergens genoemd. Misschien vanwege de positionering van de triënnale in Duitsland, een land dat bekendstaat om strenge censuur van elke kritiek op de staat Israël. Ornamenta’s focus op helende rituelen valt te plaatsen, want de voorbereidingen van de triënnale begonnen tijdens de Covid-pandemie. Wanneer een project op zulke lange termijn ontwikkeld wordt, verdwijnt de urgentie om binnen een programma op acute politieke gebeurtenissen te reageren wellicht naar de achtergrond. Toch zou ook de mogelijkheid voor een snelle respons op urgentie politieke gebeurtenissen meer ingebouwd kunnen worden in een langdurig proces. Worteling zou niet ten koste moeten gaan van het reactievermogen van een kunstmanifestatie.

Per definitie vindt een triënnale driejaarlijks plaats. Bij Ornamenta duurde het vijfendertig jaar voordat er een vervolg kwam, in plaats van twee. Of de triënnale ditmaal bestempeld zal worden als een succes, en in de toekomst verder wortel schiet, is de vraag. De meeste bomen hebben ongelijkmatige groeiringen.

Het artikel ‘Ongelijkmatige Groeiringen’ door schrijver en beeldend kunstenaar Dagmar Bosma is gebaseerd op een bezoek aan het noordelijke deel van het Zwarte Woud in gezelschap van kunstenaar Yvonne Droge Wendel, curator Jules van den Langenberg en Tubelight redactieleden Jip Hinten en Veerle Driessen.

Bosma sprak in Duitsland met Dr. Philipp Reisert, ondernemer in edelmetaalrecycling; Nina Kopp, architect; Bettina Schonfelder, directrice Kunstverein Pforzheim; Thorben Gröbel, kunstenaar; Makan Fofana, filosoof en futurist, en Yasemin Keskintepe, curator; Katharina Wahl, curator. Dit artikel is tot stand gekomen met dank aan het Stimuleringsfonds voor de Creatieve Industrie en het Mondriaan Fonds.