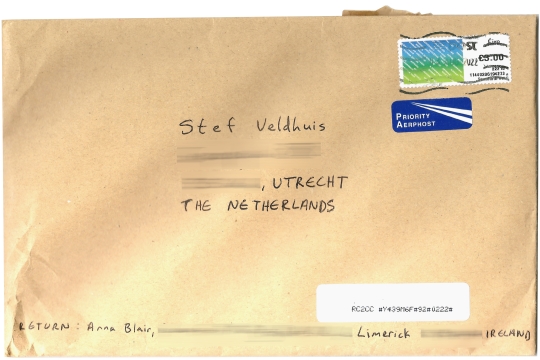

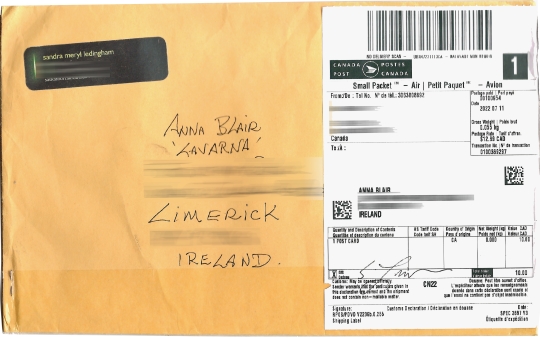

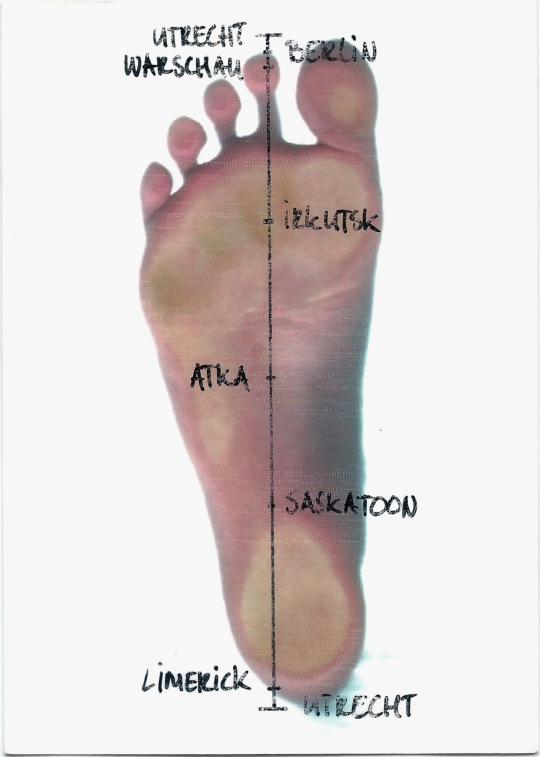

In early 2022, my friend, the artist Stef Veldhuis (1992), made a scan of the sole of his foot and mailed it off from Utrecht, the Netherlands to make its way around the world on the 52nd parallel. Through word-of-mouth and Google Maps he found six participants to take part in an experiment in distilling ‘speed, scale and distance’ into the pure form of a postcard. Each recipient would note on the postcard that they had received it, and were passing it on, tucking the previous envelope into a new one. The resulting artwork, called Distance as Object, would essentially make itself in the act of circumnavigation.

Distance as Object exemplifies Stef’s role as what American mail artist and curator Chuck Welch (aka CrackerJack Kid, 1948) has called the artist as networker. Stef prepared the way for the work to take form, mapping its route and engaging participants in an act of handling, trusting them to propel it through the bowels of the international postal network. The postcard made it easily from Utrecht to Berlin, then to Warsaw – where it was promptly halted in mid-March 2022. Stef’s Warsaw contact tried twice, unsuccessfully, to send the letter on to Irkutsk, Russia. They were told by Poczta Polska (Polish Post) workers that the letter would not arrive in Irkutsk until the ‘situation’ – namely, the unlawful invasion and attempted annexation of Ukraine by Russia in February 2022 – was resolved. At that point, Stef decided to skip Russia and send the letter on to Alaska, where it continued its journey. It arrived safely back in Utrecht in August, bearing human-orientation markers like latitude, zip codes, duties and customs. But it was missing a stamp from the Russian Post.

In late February or early March 2022, six national postal services, including Poczta Polska, wrote to the Universal Postal Union, a UN subsidiary, that they would no longer deliver mail to Russia or Belarus. They did this at the behest of the Ukrainian Post, and in doing so they instated a communications blockade still deeply significant despite the prevalence of the internet. Mail art, being reliant on nationalized postal services, is exposed to the political currents that extend to every governmental office. As Uruguayan mail artist and activist Clemente Padin (1939) claims, mail art reflects the social or political reality of the sender and the receiver. What happens when communication between the two is somehow cut? When permeable borders become impermeable?

Distance as Object’s ‘border incident’ highlights reignited tensions at the edge of the EU. It also illuminates fascinating aspects of mail art as a practice, of which I would like to discuss the following: mail art is inherently political; mail art objects absorb the weight of human conflict and tensions through encounters with war; and, perhaps most importantly, postal workers are unacknowledged yet essential participants in the making of mail art.

Fluxus artist Robert Filliou (1926-1987) believed that the purpose of art was to lift life above art, and proposed the Eternal Network, a global community of people dedicated to making ideas real. We can consider any communal endeavor that reaches beyond the limits of technique, borders, and conflict to be part of the Eternal Network (for instance: the most democratic corners of Reddit, the early days of Twitter). But it is most inextricably linked with mail art, produced by people who rely on postal services to communicate with each other. During the Cold War, artists behind the Iron Curtain used mail art to sketch a network, to access people and places they had never been able to reach in person. But I would argue that the Eternal Network is something of a misnomer, as surely a limb of it was severed when Poland refused to provide this public service to Russia in March 2022. Is the network eternal if its limits can be so clearly defined? I find that much mail art, at least from Western countries, has a certain naivety, in the sense that it takes globalism for granted.

At its strongest, however, mail art can illuminate closed social and political borders. For instance, in 1987, Brno activist and poet Petr Pospíchal (1960) was arrested and jailed by the Czechoslovak secret police. Polish Solidarity activists had been producing counterfeit stamps as collectors’ items; they smuggled their stamps across the Polish border and sent Pospíchal a letter of solidarity through the official Czechoslovakian post. Imagine receiving a letter like that: one that slipped through the fingers of prison censors and postal workers to land in your cell, bearing the literal mark of resistance. And now, more than thirty years later, the gears of bureaucracy have shut the gates on a postcard of a foot. When Stef’s postcard could not cross the border into Russia, it became part of the conflict. Art objects in general, but mail artworks especially, accrue the hallmarks and tensions of conflict and unease when they gain proximity to political instability, diplomatic failures, war. They gain political weight as permeable, absorbent social objects whose significance lies in their role in and as communication. Their very material embodies reality, imprinted by the hands and stamps that have or have not touched them; crumpled by the postal carrier bags that have or haven’t carried them.

This weight of conflict doesn’t necessarily reside in the presence of a stamp, though ‘artistamps’ (stamps made by artists) are an excellent and tangible expression of political and/or social tension. In the case of Distance as Object, the absence of the Russian stamp was the stark indicator of the object’s proximity to war. The Irkutsk recipient could not put it in an envelope, carefully address it and send it on. Touched by conflict, the work became entangled with it, a dance that deepened with the distance the envelope gained from this incident. By the time it landed in Utrecht, it had been indelibly marked by its encounter with the Poczta Polska.

And who stopped Stef’s letter in Warsaw? It is easy to resent a person unwilling to look past their instructions, but with a blockade in place, there was surely nothing they could do. I would argue that this unnamed person had as important a role in the production of the work as the invited participants themselves. I love the power play involved in providing such an achingly uncertain timeline for the continuation of the letter’s journey: ‘when the situation is resolved’. It is as confusing and opaque as the opening scenes of Kafka’s The Trial: should a complaint be filed or answers sought, no clarity could be gained. This brings me to my second point, which is that mail art, especially in regions with uneasy relationships with communication, inherently relies on – and relishes – its clash with the postal service. Furthermore, the fight or struggle with the postal service and its officials is a time-honored tradition in mail art. Sneaking past censorship and defying automation; teasing and enticing bureaucrats to use their letter-opener just this once… this is part of the appeal of this form of conceptual art practice.

Artists, especially in the Communist Bloc, had reason to be wary of nosy postal workers, who could report them for receiving too many letters (in the 1950s in Poland, it was illegal to receive foreign post; by the 1970s you still needed a good explanation for why you were getting it). And in fact, in the USSR, mail art was unable to take hold until glasnost loosened the chokehold the state had on communication. On the other hand, mail artists cannot function without the untold numbers of laborers working to complete the process of creation. In moments when the anonymous postal worker becomes not just a facilitator but a visible participant of mail art, this relationship is that much more powerful.

And yet, it seems as if mail artists are not aware of the people who are essential to the success of the work: the postal workers, government officials who spend their working lives making communication possible. Mail art pioneer Ray Johnson (1927-1995) considered postal workers to be art handlers; I find this rather arrogant, a refusal to truly embrace the extent and function of the Eternal Network. In fact, I claim that in many instances, the artist takes the postal service – and its workers – for granted, expecting the state to somehow magically facilitate the production and transmittance of the artwork in the very act of franking the envelope. In this form of mail art, it does not really matter how the work arrives as long as it does. The validity and meaning of the work, however, is to a great extent dependent on the contact it has with the hands of the employee. Michael Duquette, a Canadian postal union activist and mail artist, sent the work I Support the Postal Workers to Chuck Welch, a necessary and affirming demonstration of solidarity. In this sense, the Eternal Network is vastly larger than Filliou claimed, populated by not just senders and receivers, but carriers, facilitators, and, yes, even censors and security.

This border incident, the encounter between Stef Veldhuis’ Distance as Object and the Polish border, is woven into the materiality and meaning of the work. I am always interested in the moments where things go wrong – where discomfort and tensions rise to the surface. If the postcard had made it all around the world without incident, it would fit neatly into the happy narrative of a truly globalized world, one whose international cooperation in facilitating personal communication is a last, socialized remnant of permeable borders. As such, Stef’s foot took on extra cultural value in its unexpected encounters, as well as the burden of war. While the artwork was slowly accruing meaning and weight in each port of call, the war was building in extremity, causing untold harm to Ukrainians. As an object of solidarity, it has strong links with mail art that was testing the boundaries of oppression more than fifty years ago, a dimension of political time exposed in the polite rejection by a Poczta Polska teller.

Maia Kenney is a Polish-American independent curator, art historian and educator based in Utrecht. She is a specialist in surrealism in its intersections with sex and fetish, as well as in contemporary art and design.